Cerebrospinal Nematodiasis (Visceral Larval Migrans) in Birds

Martin Ficken, DVM, PhD, ACPV

Nematodes of the genus Baylisascaris are recognized as causes of avian cerebral nematodiasis. Baylisascaris columnaris, the ascarid of skunks and Baylisascaris procyonis, the ascarid of raccoons, have been documented as the species responsible for this disease. The disease occurs after consumption of the ascarid eggs in contaminated feed or picked up from the ground of contaminated premises. The bird is an aberrant host and as such the larvae migrate outside of the intestinal tract and often locate in the brain causing central nervous system clinical signs (Figure 1). Symptoms include ataxia, torticollis, circling, extensor rigidity, and paralysis. Birds may die quickly while others may linger for days. Outbreaks have been documented in partridges, emus, quail, and chickens and the condition has been reproduced experimentally in chickens.

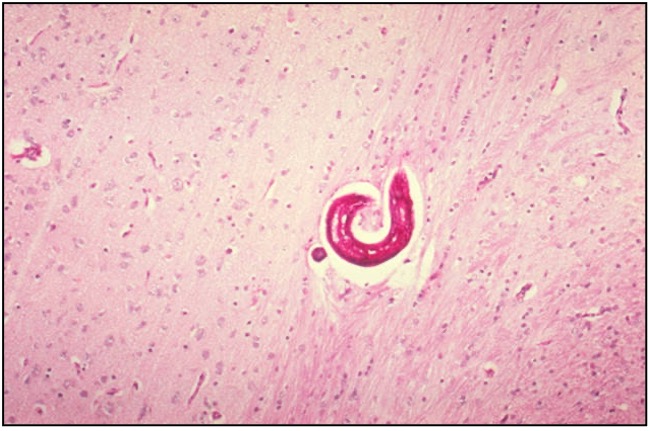

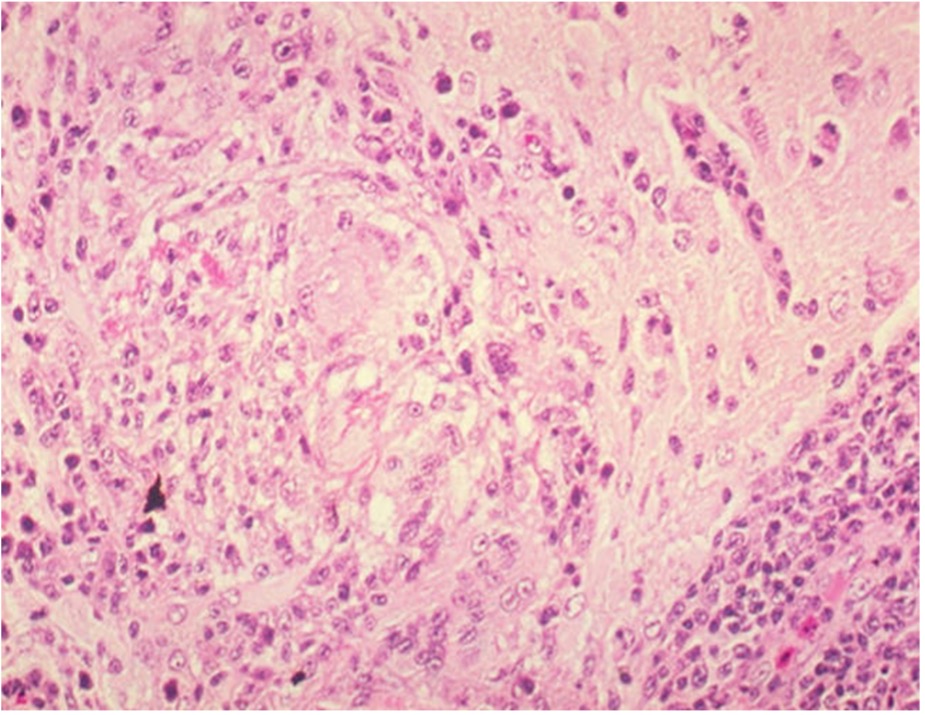

The migration of the parasites in the brain (Figure 2) eventually cause microscopic lesions consisting of necrosis, hemorrhage, granulomatous inflammation, and lymphocytic perivascular cuffing (Figure 3). Diagnosis is made on clinical signs, microscopic lesions, and a history that would include possible exposure to feces of raccoons or skunks.

Treatment and control include removing contaminated feed and/or removing birds from contaminated premises as ascarid eggs are extremely resistant to chemical inactivation, desiccation, and low temperatures. The eggs can remain viable in the soil for several months or even years.

Differential diagnoses for this disease include other neurological diseases of birds such as fungal (ochroconosis or aspergillosis), bacterial (salmonellosis, staphylococcosis, pasteurellosis), viral (Marek’s disease, Newcastle disease, avian influenza, avian encephalomyelitis), protozoal (toxoplasmosis), nutritional (vitamin E, selenium deficiencies), and toxins (organophosphates, carbamates, toxaphene, ethylene glycol).

Baylisascaris procyonis is a potential zoonotic concern as the raccoon ascarid has been shown to cause cerebral nematodiasis in human beings.

References

- McDougald LR. Internal Parasites in Diseases of Poultry, 13th edition, Wiley-Blackwell, ed. Swayne, DE et al. p. 1125, 2013.

- Kazacos KR and Wirtz WL. Experimental cerebrospinal nematodiasis due to Baylisascaris procyonis in chickens. Avian Diseases 27:55-65, 1983.

Figure 1. Bobwhite quail demonstrating clinical signs of cerebral nematodiasis (visceral larval migrans). File photographs courtesy of Dr. H. John Barnes, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University.

Figure 2. Baylisascaris nematode within the brain of a quail with no inflammatory response. File photographs courtesy of Dr. H. John Barnes, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University.

Figure 3. Granulomatous inflammation with necrosis within the brain of a quail infected with Baylisascaris. Note lymphocytic perivascular cuffing around blood vessel in the lower right-hand corner. File photographs courtesy of Dr. H. John Barnes, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University.