Histomoniasis (Blackhead) in birds

Martin Ficken, DVM, PhD

The causative agent of histomoniasis is a protozoan parasite Histomonas meleagridis. Numerous gallinaceous birds are affected by this parasite including turkeys, chickens, chukar partridges, peafowl, pheasants, and ruffed grouse. H. meleagridis is commonly transmitted in embryonated eggs of the common cecal worm, Heterakis gallinarum. Chickens and other gallinaceous birds harbor this worm, which acts as a reservoir. In turn, earthworms can act as vectors for cecal worm larvae containing H. meleagridis. After ingestion of the cecal worm eggs harboring H. meleagridis, the histomonads are released in the ceca where they replicate rapidly causing severe necrosis and inflammation and migrate into the submucosa and muscularis and eventually invade the vascular system and spread primarily to the liver where they can cause extensive damage.

Signs of histomoniasis include yellow (“sulfur-colored”) feces, depression, ruffled feathers, huddling, anorexia, and in some birds cyanosis of the head where the common name “blackhead” arose. The degree of disease in chickens is variable as they are more resistant than turkeys. Morbidity and mortality can approach 100% in turkey flocks.

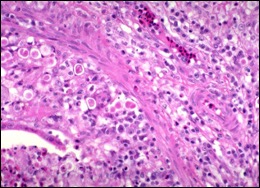

The primary gross lesions occur in the ceca and liver (Photograph 1). The cecal walls are thickened by inflammation and the lumen is distended with a cheesy or caseous core. Lesions in the liver are those of necrosis and chronic inflammation and the classic presentation is of “bullseye” lesions with a dark red center and pale outer ring. Microscopically, there is necrosis accompanied by chronic inflammation of macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells with numerous histomonads observed with vacuoles of phagocytic cells (Photograph 2) both within the ceca and liver.

There are no current licensed chemotherapeutic products available for treatment of histomoniasis, therefore, control measures are focused on prevention. During the outbreak, removal of the birds from a contaminated premise to a clean area may be helpful or thick covering of the contaminated area with deep litter may reduce spread of the disease. Since the primary reservoir of H. meleagridis is the cecal worm ova, control of cecal worms by therapeutic or mechanical means is beneficial.

Rearing turkeys separate from chickens is highly recommended as chickens are a known reservoir of cecal worms and histomoniasis is often less severe or subclinical in chickens.

For more information about poultry testing, visit tvmdl.tamu.edu or call 1.888.646.5623.

Reference:

Hess, M, McDougald, LR. Histomoniasis (Blackhead) and Other Protozoan Diseases of the Intestinal Tract in Diseases of Poultry, 13th edition, Wiley-Blackwell, ed. Swayne, DE et al. pp. 1172-1182, 1197-1198, 2013.