Pathologic diagnosis of coccidiosis in goats

Kellie Richardson and Erin Edwards, DVM, MS, DACVP

Coccidia are single-celled parasites that are common in many species, including goats. Diagnosis of coccidiosis is most commonly achieved through fecal flotation in specimens from live animals. Characteristic lesions can also be seen at necropsy. This article will highlight a recent case of coccidiosis in a goat kid at the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) which demonstrates typical features of caprine coccidiosis. TVMDL has seen many cases of coccidiosis in goats this spring.

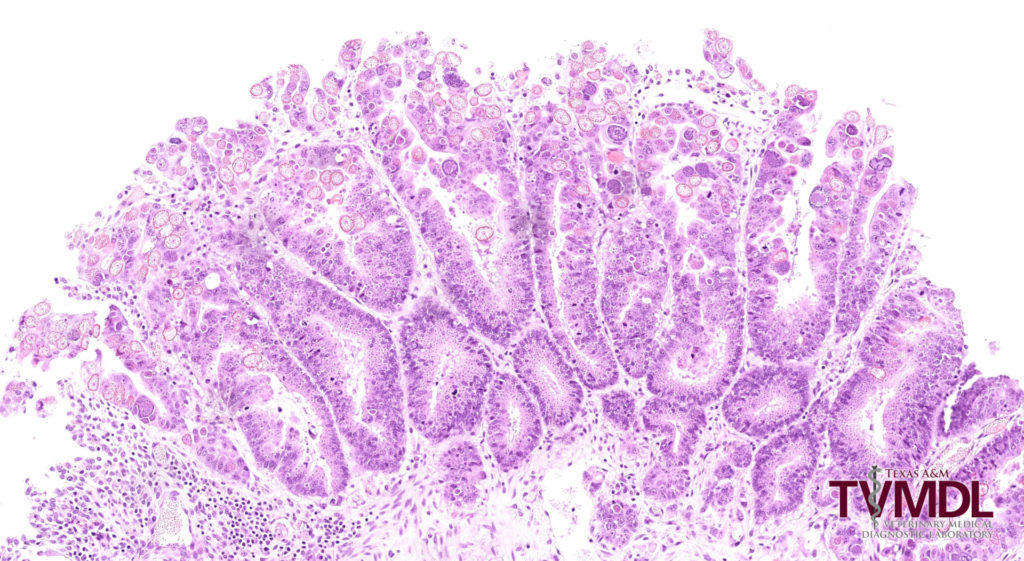

The goat in this case was a 2-month-old, female, Boer goat kid that was submitted for necropsy. This goat and other animals in the herd were reported to have recent diarrhea. Upon postmortem examination, liquid fecal material was adhered to the hair around the anus. Dissection of the small intestine revealed numerous raised, smooth, white nodules on the mucosal surface of the jejunum (Figure 1). These nodules averaged 2-3 mm in diameter and could occasionally be seen through the serosal surface before the lumen was opened. These gross findings are uniquely characteristic of coccidiosis in goats. In most other animal species, lesions of coccidiosis do not result in raised masses. Histopathology and fecal flotation were performed in this case, both of which confirmed the diagnosis of coccidiosis. Histologically, the raised nodules corresponded to proliferative clusters of intracellular coccidia organisms (Figure 2). Multiple developmental stages were present, resulting in a varied and colorful histologic lesion.

Coccidiosis is caused by microscopic protozoan parasites called coccidia. Coccidia are host-specific and each animal species is susceptible to infection with various coccidia species. In goats, Eimeria spp. are most common. This protozoan parasite goes through its life cycle in the small intestine, undergoing asexual and sexual reproduction, ultimately laying eggs called oocysts. Growth and multiplication take place in the gastrointestinal tract, destroying the epithelial cells. Transmission of oocytes is via the fecal-oral route. This process involves oocysts being passed when an animal defecates, and another animal ingests the contaminated substrate. The destruction of cells lining the intestines combined with damage to tissues give rise to the indicative symptoms of coccidiosis. Clinical cases can vary from loss of appetite and decrease in weight gain to severe cases involving chronic diarrhea, fluid feces containing mucus and blood, straining in attempt to pass feces, loss of weight, and dehydration. Coccidiosis is prevalent among young animals, likely attributed to weakened immune systems and increased stress. Diagnosis is based on history, clinical signs, microscopic examination of feces, and, in severe cases, post-mortem analysis. Since transmission is through defecation, it is important to have good sanitation and isolation of sick animals to help prevent spread through herds. Coccidia eggs are resistant to many disinfectants and can survive more than a year in dark, moist environments. Regular removal of manure and wasted feed, not feeding on the ground, and designing feeders and water systems that minimize fecal contamination are all great preventative measures. Treatment with coccidiostats seems to be effective. Before administering treatment, consultation with a veterinarian is recommended to ensure appropriate diagnosis, drug selection, and dose.

For more information about this case, contact Kellie Richardson, histopathology technician, or Dr. Erin Edwards, anatomic pathology assistant section head. To learn more about TVMDL’s test offerings, visit tvmdl.tamu.edu or call 1.888.646.5623.