Rabies in a Sheep

R. G Helman DVM, PhD DACVP

An 8-month-old male sheep was purchased out of state at the end of September. The animal was clinically normal until November 1 when it was noted to be having a seizure. The animal could not stand or walk and was observed to be chewing on its rear legs. The clinical signs progressed until November 4 when the animal died. The clinical concern was for an infection with the nematode Parelaphostrongylus tenuis with involvement of the nervous system.

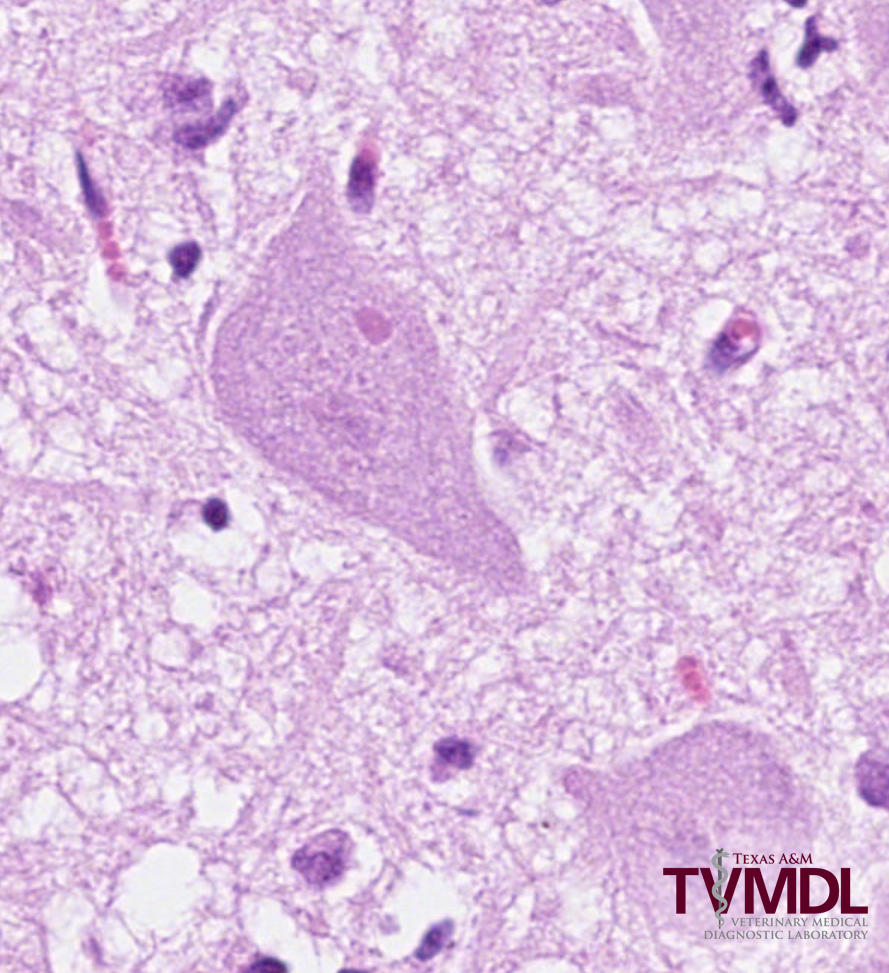

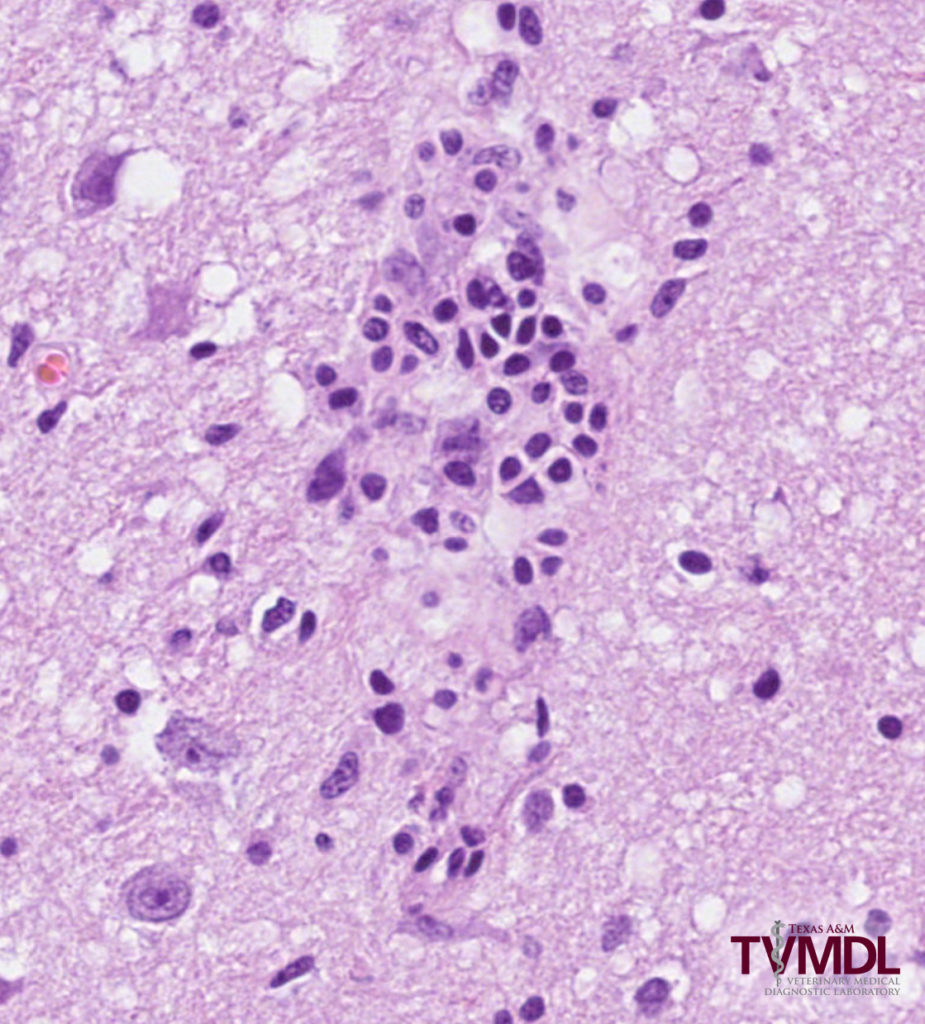

A necropsy was performed and fresh and fixed tissues consisting of brain, heart, liver, lung, spleen and kidney were submitted to the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) for testing. A sample of fresh cerebrospinal fluid was included with the submission. Examination of tissue sections from the submitted fixed tissues showed no significant changes in the heart, lung, liver, spleen or kidney. However, there was evidence of mild patchy inflammation in various regions of the brain. The inflammation was characterized by perivascular and parenchyma infiltrates of mononuclear leukocytes, primarily lymphocytes with fewer mononuclear phagocytes. Inflammation was noted in gray and white matter and in the former, leukocytes were present in nuclear areas (Figure 1). Intracytoplasmic inclusions were noted in individual neurons. (Figure 2).

Based on the histopathological lesions, a presumptive diagnosis of rabies was made and the unfixed half of brain was submitted to the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) laboratory for testing. Sections tested positive using a fluorescent antibody procedure.

Several aspects of this case are commendable for learning opportunities. The endemic nature of Parelaphostrongylus tenuis infection in white-tailed deer certainly raises the issue of an etiology in a naïve animal with neurologic signs. However, the rapid onset and progressive nature of the clinical neurologic signs should also raise a suspicion of other etiologic agents including rabies. One potentially serious problem with this case was the division of the brain to include half of it fixed and half fresh.

Because the rabies virus is not always uniformly distributed in brain tissue, the Texas DSHS laboratory requires a complete (left and right hemispheres) cross-section of fresh brain that includes the cerebellum and brainstem. Partial sections will be accepted for rabies testing, but if there is no fluorescent antibody reaction, the results will be reported as “Unsatisfactory Sample,”as the DSHS laboratory is unable to definitively determine that the brain is negative for rabies. As a result, the rabies status is left open and the situation will then require potential intervention by state public health officials to gauge the exposure risk and need for treatment.

In the current case, even though only half of the brain was submitted, a positive diagnosis was able to be made, allowing for a timely diagnosis.

This case highlights the importance of submitting the entire brain in a fresh, unfixed state for an animal with progressive neurological disease over a short time period. Unless rabies can be definitively eliminated as a possibility, it should always be included in the differential diagnosis and testing then pursued for confirmation.

TVMDL recommends submitting the entire head for small animals, small ruminants, and wildlife species. For large animals, unless the head can be delivered directly to TVMDL, it is best to remove the brain in its entirety and ship fresh and chilled. In packaging the brain for shipment, it should be protected from being crushed/smashed by packing materials such as frozen cold packs.

To learn more about rabies testing, visit tvmdl.tamu.edu or call the Amarillo laboratory at 1.888.646.5624 or the College Station laboratory at 1.888.646.5623.

Figure 1. Photomicrograph depicting leukocytes present in nuclear areas of a brain sample submitted to TVMDL.