Meningeal Worm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) in a Sitatunga

Terry Hensley, MS, DVM and Gabriel Gomez, DVM, PhD

A less than one-year-old, 48 lb. female sitatunga (Tragelaphus spekii) in fair to poor body condition was submitted to the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) for necropsy. The clinical history indicated the animal was found in a bog area with suspected radial nerve paralysis of the right front leg. Clinically, pneumonia was a top differential due to the poor body condition of the animal. The animal was euthanized due to a poor prognosis based on the animal’s clinical condition. The primary lesions observed at necropsy were generalized serous atrophy of fat, consistent with negative energy balance, and corneal opacity of the right eye. No evidence for an infectious disease process was encountered in this case.

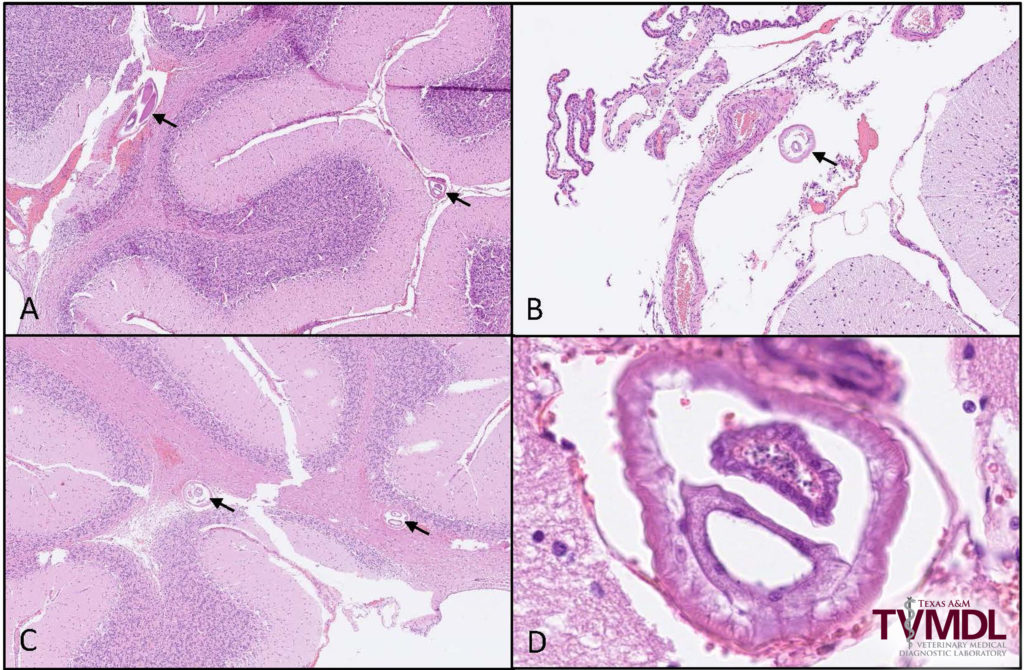

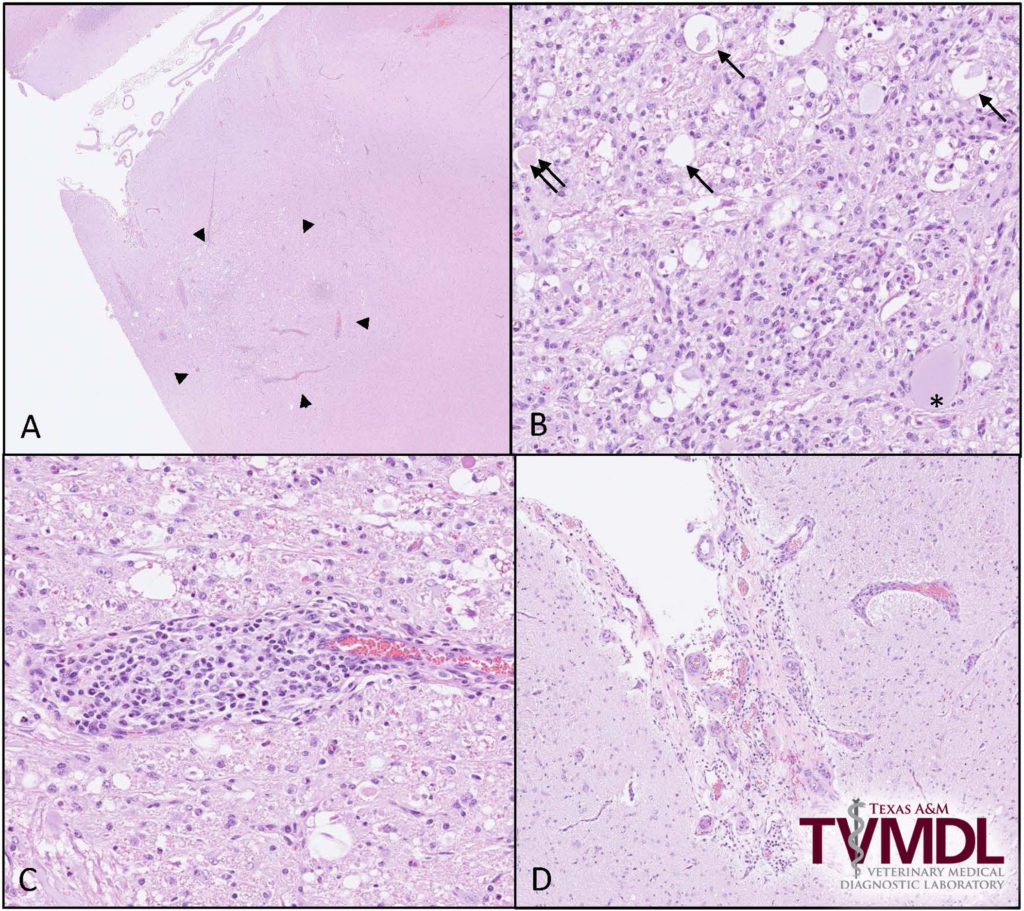

The most important histologic lesions were found in the brainstem and consisted of multifocal areas of inflammation with hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 1). The inflammatory infiltrate was primarily composed of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells and fewer eosinophils. Inflammatory cells surrounding blood vessels (perivascular cuffs) was not an uncommon finding (Figure 1). A few cross sections of a nematode parasite, morphologically consistent with Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, were found in the cerebellum (Figure 2). Other microscopic findings in this animal were interpreted as incidental and consisted of eosinophilic inflammation in the intestines and mild pulmonary edema and hemorrhage.

Meningeal worm (Parelaphostrongylus tenuis) is a parasite of white-tailed deer (WTD). As the natural host, they normally tolerate the parasite without exhibiting signs of disease. Other cervid species, numerous antelope species, sheep, goats and camelids may become infected and develop severe neurologic disease with a high mortality rate due to central nervous system (CNS) damage from the migrating parasite. Consistent with the distribution of white-tailed deer populations, this is predominantly a disease of eastern and central North America.

White-tailed deer acquire the infection by accidentally consuming terrestrial snails or slugs infected with third stage larvae. The larvae penetrate the abomasum and migrate along nerves to the spinal cord where they continue to develop for approximately 40 days before migrating to the brain. The adult worms are located on the surface of the spinal cord, the meninges and in the cranial venous sinuses where the eggs are deposited. The eggs are carried to the lungs by the venous circulation where they embryonate and hatch as first stage larvae. The larvae migrate up the respiratory tract, are swallowed, and passed in the feces. The larvae penetrate the foot of the required intermediate host (terrestrial snails and slugs) where they develop to the infective third stage larvae in about 30 days. The infection is acquired in the same manner by other susceptible species, but the larvae rarely develop into reproductive adults, which is an event that allows for continued aberrant migration of immature parasite forms and disease development in susceptible species. It has been shown that some elk, and possibly other aberrant species such as moose, can survive infection with meningeal worm and produce a patent infection whereby larvae are passed in the feces.

Ante-mortem diagnosis of this disease in WTD may be done utilizing the modified Baermann technique and identifying the first stage larvae retrieved from the feces by molecular techniques. The diagnosis is usually made on postmortem exam by finding adult worms on the cranial meninges.

Diagnosis in other susceptible species is by postmortem recovery of adult worms from the cranial meninges, which uncommonly happens in species other than WTD, or by observing histological lesions in brain and/or spinal cord consistent with meningeal worm infection.

Prevention of clinical disease in some susceptible species such as llamas and alpacas has been attempted through the use of anthelmintics every 4 to 6 weeks in the hopes of targeting the third stage larvae before they migrate to the spinal cord and brain. This protocol may inadvertently lead to anthelmintic resistance in more common intestinal parasites and should be used with caution, if at all.

For questions about this case, contact Dr. Terry Hensley, veterinary diagnostician at the College Station laboratory, or Dr. Gabriel Gomez, veterinary pathologist by calling 1.888.646.5623. To view TVMDL’s full catalog of tests, visit tvmdl.tamu.edu.

Figure 1. Brainstem exhibiting lesions associated with meningeal worm migration. A. Low magnification of brainstem with an area of necrosis (arrowheads). B. Microscopic lesions resulting from parasite migration include dilation of myelin sheaths (arrow), central chromatolysis of neurons (*), swollen axons (double arrows) and inflammatory cells composed of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells and eosinophils. Inflammatory cells surrounding blood vessels (C) and expanding the meninges (D) were frequent findings.