Rhinosporidium diagnosed in Texas horses

By Gabriel Gomez, DVM, PhD, DACVP

With over 800,000 tests run annually, TVMDL encounters many challenging cases. Our case study series will highlight these interesting cases to increase awareness among veterinary and diagnostic communities.

Fixed tissue samples from nostril masses of three horses were received at the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) for histopathologic examination. The animals were a 23-year-old Quarter Horse gelding, an 18-year-old Appaloosa mare, and an adult American Quarter Horse gelding of unspecified age. The histories provided with the specimens were brief, but described a nostril mass in all three cases. The mass from the 23-year old Quarter Horse was further described as being pedunculated. The histories provided failed to reveal whether these masses were associated with any clinical signs or how long it took for lesions to develop. There was no correlation as to the time of year as the three specimens were submitted in the winter, early spring, and mid-summer.

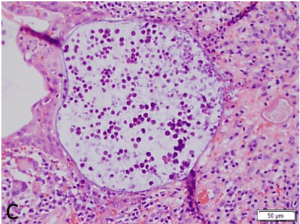

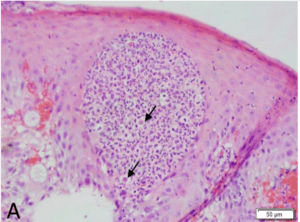

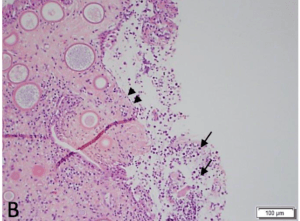

Microscopy of the tissue sections from specimens on all three cases revealed a mixed inflammatory infiltrate that replaced the submucosa of the nasal cavity. In all three cases, this inflammatory infiltrate consisted of variable numbers of neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells. The inflammatory cells were accompanied with granulation tissue, areas of mature fibrous connective tissue, necrotic debris and hemorrhage. Multifocally within the submucosa were parasitic sporangia that were up to 300µm in diameter and contained endopspores. These organisms were morphologically consistent with Rhinosporidium seeberi. The overlying epithelium was moderately hyperplastic and formed hyperplastic nodules in two of the three cases. There were areas of squamous metaplasia in all three cases and one of the samples had an ulcerated surface where the epithelium was replaced with fibrin, necrotic debris and neutrophils. Based on the composition of the inflammatory infiltrate and presence of parasitic organisms morphologically consistent with Rhinosporidium seeberi, all three cases were diagnosed as Rhinosporidiosis.

Rhinosporidiosis is caused by the protistan parasite, previously believed to be a fungal organism, Rhinosporidium seeberi. This organism has been reported to cause nasal infection in human beings, horses, mules, cattle, dogs, goats, water fowl, and cats. However, the horse is the most commonly affected species. While infection in dogs is confined to the nasal cavity, the pinna, skin, and other mucosal surfaces have been described as sites of infection in other animals. The pathogenesis of the disease is poorly defined, but contaminated water or dust particles are thought to harbor the organism. Local trauma may be a predisposing factor that may facilitate spore access to the submucosa. Once the organism penetrates the mucosa, it develops into endospore-containing sporangia. Endospores are subsequently released to the tissue or into the nasal discharge. On gross inspection, the lesion can vary from barely distinct raised lesions to larger polypoid nodules that may be mistaken for a neoplasm. These polypoid nodules have been described as soft, sessile or pedunculated that range from 0.2 to 3.0 cm. The infection is usually unilateral and the lesions may be easily visible in the nostril or may be deeper in the nasal cavity. In the latter cases, rhinoscopy may be necessary. Common clinical signs associated with infection include sneezing, serous to purulent nasal discharge, epistaxis and dyspnea.

Sections of fixed tissue for histopathology is one of the most common ways to diagnose rhinosporidiosis. Other means of diagnosis include cytology of nasal exudate to detect sporangiospores or PCR testing on fresh tissue. Currently, only histopathology and cytology are offered at the TVMDL.

To learn more about this case, contact Dr. Gabriel Gomez, veterinary pathologist at the College Station laboratory. For more information on TVMDL’s test catalog, visit tvmdl.tamu.edu.

Nasal Epithelium. The epithelium contains a pocket of inflammatory cells comprised primarily of neutrophils. Admixed with the inflammatory are few free endospores (arrows).

Nasal Cavity. The epithelium is ulcerated (double arrowheads) and the surface contains few inflammatory cells, necrotic debris and free endospores. The submucosa contains developing sporangia.

.

References

-

-

- https://www.askjpc.org/vspo/show_page.php?id=557

- Caswell JL, Williams KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxiw MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:579-581.

- Lopez A, Martinson SA. Respiratory system, mediastinum, and pleurae. In: Zachary JD, ed., Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2017: 490.

-