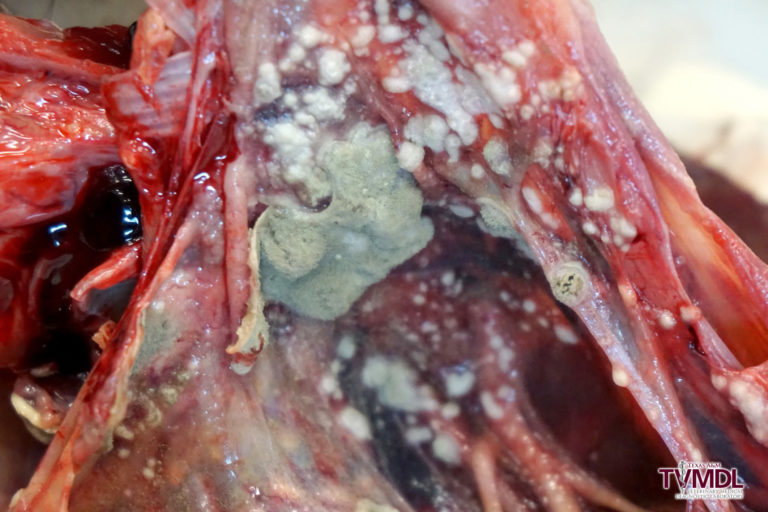

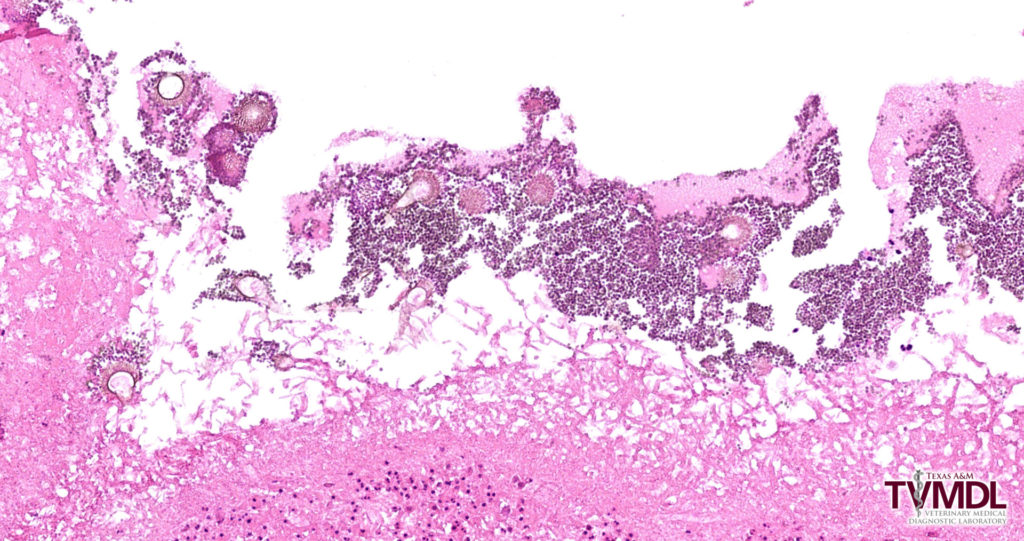

A four-year-old Pacific eider (sea duck) was reported to have a history of open-mouth breathing. It had been treated for suspected aspergillosis prior to death and was submitted to Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (TVMDL) for necropsy. At necropsy, the clinical suspicion of aspergillosis was confirmed. All air sacs were coated by green, velvety, fungal colonies that released spores upon manipulation (Figure 1). Some air sacs were also covered by thick layers of fibrin, and inflammatory exudate extended into the lungs. Histopathology showed abundant fungal hyphae coated by layers of conidia (Figure 2).

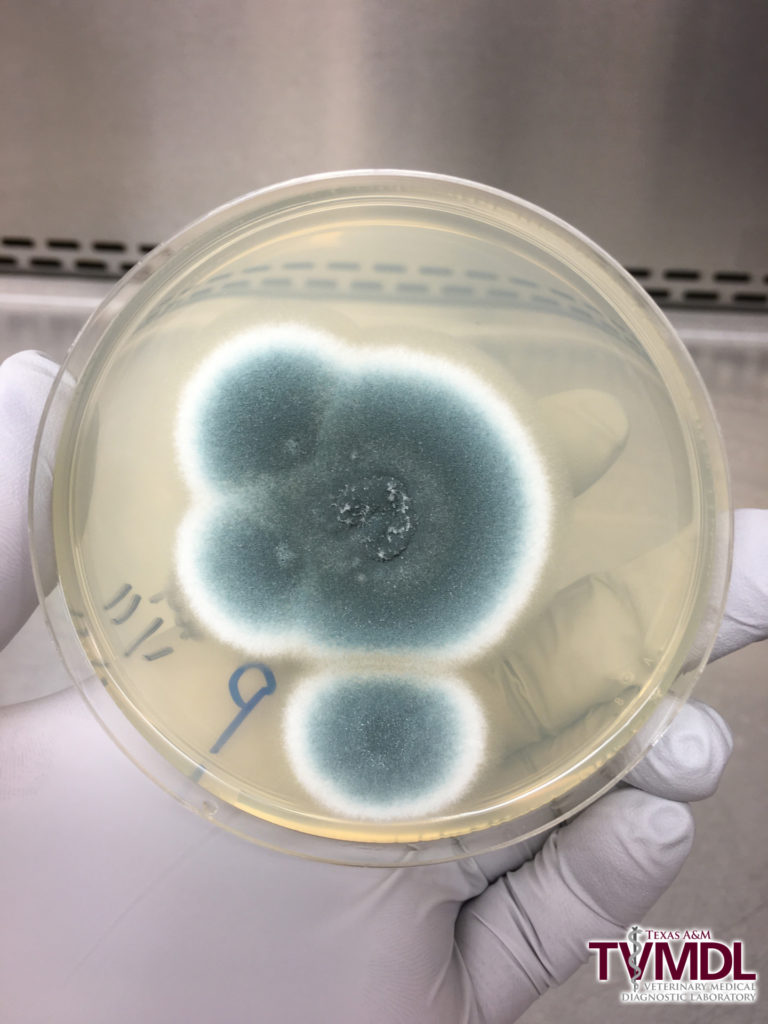

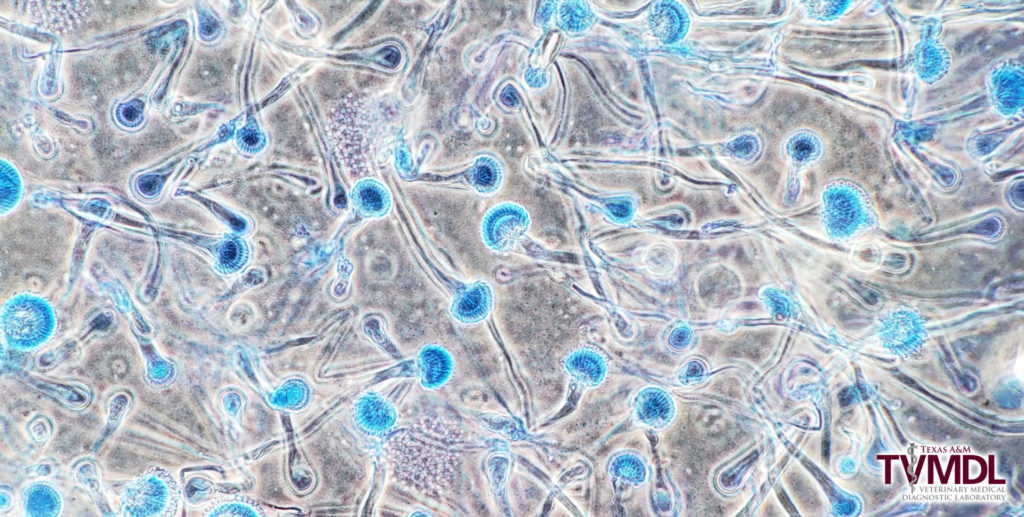

To isolate Aspergillus, a swab from an affected air sac was streaked onto four different agar plates and incubated at room temperature. On the third day, pure colonies of Aspergillus were observed on the plates. Aspergillus are ubiquitous fungi and grow rapidly on the laboratory media including sabouraud dextrose agar and potato dextrose agar with downy- to powdery-textured colonies. The morphology of the isolated fungi in this case was very similar to Aspergillus fumigatus characterized by blue-green colonies, columnar conidial heads, and uniseriate phialides (Figures 3-4). Confirmatory PCR was not performed to identify the species.

Eiders are highly susceptible to aspergillosis. Aspergillosis is common in other captive aquatic birds, especially penguins, and can also be seen in a variety of other avian species. In birds, most cases are caused by A. fumigatus. Recognized predisposing factors include poor ventilation, high environmental spore loads, high ammonia levels, malnutrition, and underlying disease. Stress from captivity, overcrowding, temperature changes, humidity, etc., can also be an important cause of immunosuppression that predisposes birds to disease. Even under pristine management conditions, occasional cases of aspergillosis will occur among highly susceptible species such as eiders.

Aspergillosis in eiders is often a chronic disease lasting weeks to months. Once an animal shows clinical signs, the disease is often advanced. Treatment may result in minor improvement but is typically unrewarding in advanced stages of disease. Long-term treatment is needed and is often unsuccessful if begun late in the disease course. Furthermore, some cases of antifungal drug resistance are recognized. The best strategies for disease control are prevention, by minimizing stressors and other diseases, and early detection and treatment.

For more information about TVMDL’s test catalog, visit tvmdl.tamu.edu or call 1.888.646.5623.

REFERENCES

Stidworthy, M. F., & Denk, D. (2018). Sphenisciformes, Gaviiformes, Podicipediformes, Procellariiformes, and Pelecaniformes. In K. A. Terio, D. McAloose, & J. St. Leger (Eds.), Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals (p. 666). London, UK: Academic Press Elsevier.

Fenton, H., McManamon, R., & Howerth, E. W. (2018). Anseriformes, Ciconiiformes, Charadriiformes, and Gruiformes. In K. A. Terio, D. McAloose, & J. St. Leger (Eds.), Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals (pp. 708-709). London, UK: Academic Press Elsevier.